I took this panorama (Figure 1) of the Golden Gate Bridge with a Canon PowerShot.

|

| Figure 1 |

The Gear

Here's what you'll need to get started:Hardware:

Canon PowerShot SX-280HS, or any other small digital camera.

Panorama Stitching Software (pick one):

Microsoft ICE (Free, and highly recommended)

Hugin (Free)

Other Software (Pick one):

Adobe Photoshop ($10 a month)

GIMP (Free)

You'll also need a computer on which to run those software packages. Judging by the fact that you're reading this, you most likely already have one.

Notice there's no tripod. We'll be covering this later, but don't worry. You won't have to prop the camera up against a doorframe. Now grab your camera and go find a suitable panorama spot. Let's get started.

The Shoot

- If you shoot this entire scene as one photograph, then crop it to a desirable ratio in an image editing program, you won't have a suitable panorama in the end. It won't be of high enough resolution to print higher than about 2x8, depending on the camera you're using. Panoramas are built by taking a number of shots, one of each part of the scene, then stitching them together to form the whole picture. So with that in mind, we'll get the highest resolution pano by zooming in as much as we can (without using digital zoom - it's a lie), and starting the shoot that way. You should know your camera well enough to know when you've reached the maximum zoom allowed, without going over into digital zoom. Find the entry about it in the manual if you don't know. You'll probably get the best results using between 10x and 20x zoom, so keep that in mind if you have a camera like the Nikon P900, which has an absolutely insane 83x zoom.

- How about exposure? We know that the most precise panoramas are best done with manual exposure, so that the camera doesn't guess a little differently between shots, and end up giving you some shots that are darker than others. This behavior comes to light most obviously when you're shooting superzoomed, getting sky in one image, only bridge in the next, and then only a boat sail in another one. The camera will guess differently for each of those types of shots, and that's not good. For this particular shoot, I decided that the different shots wouldn't be enough different in exposure to worry about, so I let the camera decide. I was also trying to keep it as simple as I reasonably could.

- Now that you're zoomed in, you'll be taking shot number one in your panorama. Go to the upper left of your anticipated scene, and then move up and to the left a little more. This will give you some room to crop later, which you'll need because the shots never precisely line up, and they'll line up a little less when you're handheld. Always better to have too much in the scene and crop, than to have too little. Our finished cropped resolution will be the same as if you hadn't included the extra, so there's no penalty for overshooting when shooting a pano.

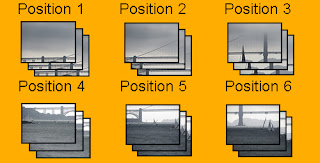

- For that first shot, and every subsequent shot, take at least three frames in quick succession. Whether you have to simply hold the shutter release button down, or press it several times, will depend on your camera. You're taking at least three because we don't have a tripod, and we need to be sure we have at least one in perfect focus. Having three will help ensure that this will occur, provided you're not in high winds or riding in a car. (Figure 2.) If you want to take more than three, go for it.

Figure 2 - Take overlapping shots, overlapping about a third of the scene between each shot. Usually you don't need this much overlap, but I try to always have too much, because if you have too little, all your effort will be wasted if the stitching software can't figure it out. Go from left to right, then come back to the left-hand side, overlapping about a third of the vertical from the first shot, and do the next row. You may only have two rows, or you may have more. It depends on the scene you're shooting, and your camera's ability to zoom. (Figure 3.) It's also possible to take the shots in vertical (portrait) orientation, but since the end result will be in landscape, I find it easier to mimic that layout when shooting. If you prefer the other way, go for it.

Figure 3 - Once you've started shooting, do not stop until you're done. If you put the camera down, you'll never know exactly where you were, and getting distracted is also a sure way to have a cloud cover the sun, making you start over. I had 16 different shot positions for this panorama, with three of each position, making a total of 48 pictures.

- After having taken all the shots, check them for focus by zooming in on the viewfinder. If they seem close, with one or two of each set in good focus, you're done. If they're all a jumbled mess, you might want to work on your handheld technique. Notice that I didn't say this was going to be a cakewalk, I said it was possible. It will take effort. You may have to start over and work a little harder.

If the shots look good, you're done in the field. Put all your gear in your shirt pocket, and let's go home and see what we can make out of this.

Processing

There isn't much in the way of processing, since you only have JPEGs. For what we're doing, processing will mean culling the junk away so that the best images are left.

Transfer all the images you shot onto the computer, so that you can look at them individually. If you have software that helps you do this, great. If not, you can use Windows Explorer to view the directory you just dumped them in, and you'll need to look at every one of them to pick the best-focused shot from each set of three. You're welcome to delete all the ones that fall short, leaving only one full set of well-focused images for use in creating the pano. More than likely, you have JPEGs that came out of the camera, as very few small cameras shoot in RAW. The JPEGs will have artifacts which we will remove later, so don't worry if you don't have RAW. Professionals will almost always use RAW, because it gives much greater latitude in editing, but we won't have to deal with that here. The tools you have will work just great.

No matter your organizational technique, make sure you have exactly one full set of images in a directory so that we can begin postprocessing. Don't have anything else in that directory.

PostProcessing

There are three basic steps here - doing the pano, fixing any issues with the result, and making the whole thing look pretty.

- Open the pano software you chose, and follow the instructions to load the pictures you took. let the program do its work, and very quickly you'll be presented with the result. If you followed the instructions above, there shouldn't be any issue with what you see. If there's a missed spot, then you'll need to go out and do it again, learning from that mistake. If you know the shots are good, but the pano software shows oddities in the intersections between shots, then try other software. Even the free software is exceptionally good, but always try something else if you don't get satisfactory results.

The edges in the result of the pano software will look jagged, as in Figure 4. Don't worry - we'll take care of that later. Many pano software packages have the ability to straighten and crop images before they're saved. If the one you've chosen has that ability, go ahead and use it now. If not, wait until we open the image in an editor.

Figure 4

- Save that image as a TIFF, or other high-quality lossless format. Don't use JPEG at this point - we've already lost some information by virtue of using that format to begin with, and recompressing it will only degrade the image further. Once the image has been saved, close the pano software.

- The following steps are necessary for finalization of the image. I won't go into detail about exactly how to do it for a couple of reasons. First, the exact method varies between programs, whether you're using GIMP or Photoshop, and explaining each would take more time than we have here. Second, I encourage you to experiment with the program you choose, to help you learn it more thoroughly. I believe that's a great way to learn - get an outline, and fill it in by experimentation. So let's continue. Open the TIFF file in an image editor, and do these steps:

A. Straighten the image

B. Crop it to a meaningful ratio, say 3:1 or 4:1, taking care to frame the result in the most meaningful way.

C. Adjust levels so that blacks are all the way black, and white are all the way white. The camera most likely wasn't too good at this, so we need to fix it. you're welcome to move away from this rule and not have any full black or whites, or even blow out the black or whites. The final choice is up to your taste. But know the "rule," so that you know why you're breaking it.

D. Clone away any imperfections that bother you. These may include ghosting from the pano software, people, trees, or any other imperfections.

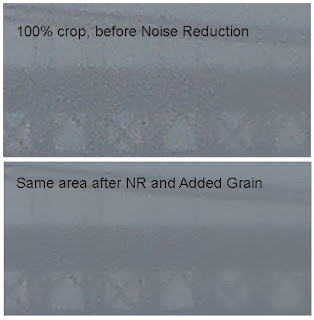

E. Remove the artifacts caused by the camera's JPEG compression. In a shot like this, the color range and brightness range is quite limited, because of the fog. This exacerbates the JPEG artifacts. The best way to do this is with noise reduction, provided you don't use so much that you lose detail. It can also be helpful to add a little noise to the image at the same time, reducing the eye's ability to see the imperfections. See Figure 5. You can tell that the result isn't perfect, but it's a darn sight better than what we started with.

Figure 5 - The final step for me was adding a color gradient filter (black into brown into yellow) to change the feel from fog to sunset. Spend some time adjusting where the three colors fall in the brightness spectrum to get the best result. There's no rule here - whatever you feel is the most aesthetically pleasing is the right way to do it.

|

| Final Panorama - Figure 6 |

The size of this image at 300 dpi is 10x40 inches, and if we print it at 150 dpi, still perfectly okay for a large panorama, we get 20x80 inches. How big your image is will depend on how many shots you took and the resolution of each shot.

Not only would I be proud to display this image, I'm actually selling it at shows right now.

And you can do the same thing!